They have helped find some of the most important fossils in the human family. They have no degrees but instruct visiting researchers. Now, the fossil technicians of the Sterkfontein Caves may finally get the academic recognition they deserve.

Fossil technician Sipho Makhele deep underground in the darkness of the Sterkfontein Caves near Johannesburg. The caves are part of the Cradle of Humankind, one of South Africa’s 12 Unesco World Heritage Sites. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

11 July 2025 • Photos and text by Ihsaan Haffejee

Itumeleng Molefe remembers the day neighbours came rushing into his family’s home in Rustenburg, a town northwest of Johannesburg. His father was famous because they had just seen him on TV, they said. “People were screaming, yelling and celebrating. It was very cool to experience.”

Nkwane Molefe, Molefe’s father, and his colleague Stephen Motsumi had just made one of the greatest discoveries in our bid to understand human origins. Fossil technicians at the Sterkfontein Caves, the pair worked under paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke to unearth the fossil skeleton of an ancient hominin known as Little Foot.

Discovered in the 1990s, it is the most complete hominin fossil yet found, with 90% of the skeleton unearthed. Little Foot was a female Australopithecus who died nearly four million years ago. Her brain was about the size of a chimpanzee’s but she walked upright on the ground, like us.

The Sterkfontein Caves near Johannesburg lie within the Cradle of Humankind, one of South Africa’s 12 Unesco World Heritage Sites. Some of the science’s most important fossils have been discovered there.

Fossil technician Itumeleng Molefe working in the Sterkfontein Caves, as his father did before him. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

Today Molefe continues the work of his now-retired father. He too is a fossil technician in the caves, searching for fossils that may help unlock the mysteries of our past.

“Our work is important,” he said. “It helps our understanding and knowledge of the world we live in. The best part of my job is that we are constantly learning, discovering new things.” He added: “You have to have passion for this job to do it well, because it’s not easy.”

Fossil technicians play a vital role in Sterkfontein, doing far more than just extracting rocks. They spend hours painstakingly separating fossil from rock without damaging the fossil. They then cast replicas of the fossils for scientists to study, with the precious originals stored away for safekeeping. They also catalogue the finds, making sure everything is properly labelled and organised.

Fossil technician Abel Molepolle with an undated photo of his father David Molepolle, who joined the Sterkfontein Caves team in 1967. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

Many of the fossil technicians have been doing this job for decades, amassing huge knowledge of the caves and their fossils.

Dr Job Kibii, head of the Sterkfontein Caves, said the technicians’ knowledge and experience was an invaluable resource for researchers. “These guys might not have degrees, but they actually know everything. In fact, a number of them have actually taught the professors and researchers who come to the site.

“They show them how to distinguish between different fossils: which are from [non-human] animals, and which are from hominins. And then the professors eventually would go ahead and do the description. But initially they learned from these guys that this is what you should be looking for.”

Fossil technician Abel Molepolle casting a replica of a fossil from the Sterkfontein Caves. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

The legacy of colonialism and the skewed power dynamics of race and class have meant that, over the years, the work of fossil technicians – often black and with no formal higher education – has not been recognised. Their important contributions have been relegated to the footnotes of the pages that document their findings.

Technician Andrew Phaswana with fossil casts. Phaswana and his team create moulds from the original fossils and then cast replicas. These are used for scientific study while the precious originals are stored for safekeeping. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

‘It is an academic contribution’

Kibii said the scientific community’s lack of recognition had been a disservice to fossil technicians. He is now actively working to educate scientists doing research at the site on the importance of the technicians’ work.

“I want them to be included in the actual publications, in the actual descriptions of those specimens, so they can be recognised with academic contribution,” he said. “Because it is an academic contribution.”

Sipho Makhele excavates in the Sterkfontein Caves’ Silberberg Grotto, close to where the Australopithecus fossil Little Foot was discovered. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

“We are not asking for much,” said technician Sipho Makhele. “We are just asking to be acknowledged for the work we do.”

Makhele too has family ties to the site, as the third generation to work in the caves. It may go on to a fourth. “Now my young daughter is also interested and has begun her university studies in anthropology,” he said.

“So, we will keep digging and digging. There’s still plenty to find down there.”

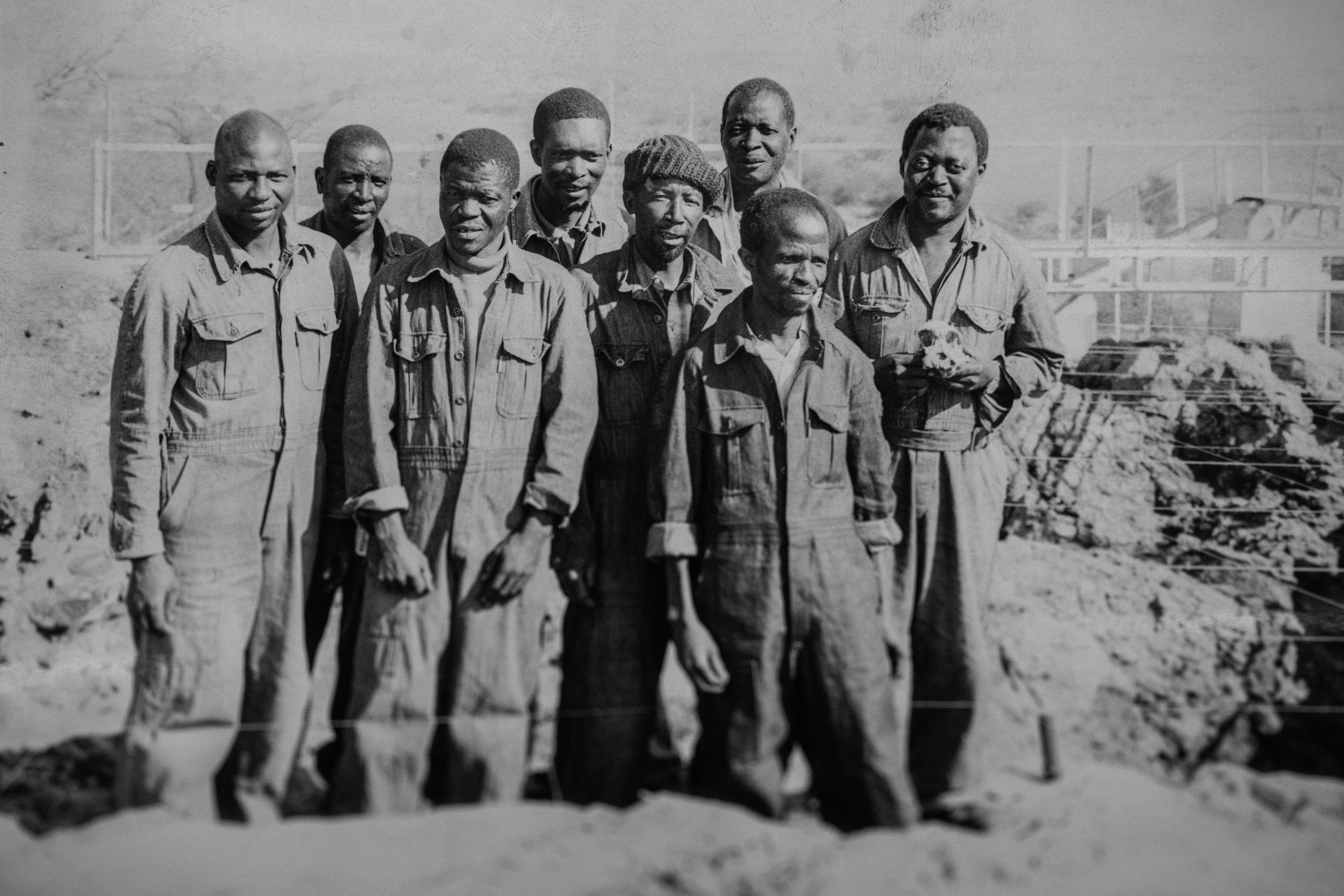

An undated old photo of fossil technicians at the Sterkfontein Caves. Itumeleng Molefe’s’s father, Nkwane Molefe, is second from right. Steven Motsumi is fifth from right. The pair unearthed the famous Australopithecus fossil Little Foot while working under paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke.

Inside the Sterkfontein Caves, where some of the world’s most important human fossils have been discovered. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

Originally published by GroundUp on 30 June 2025.

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You must be logged in to post a comment.